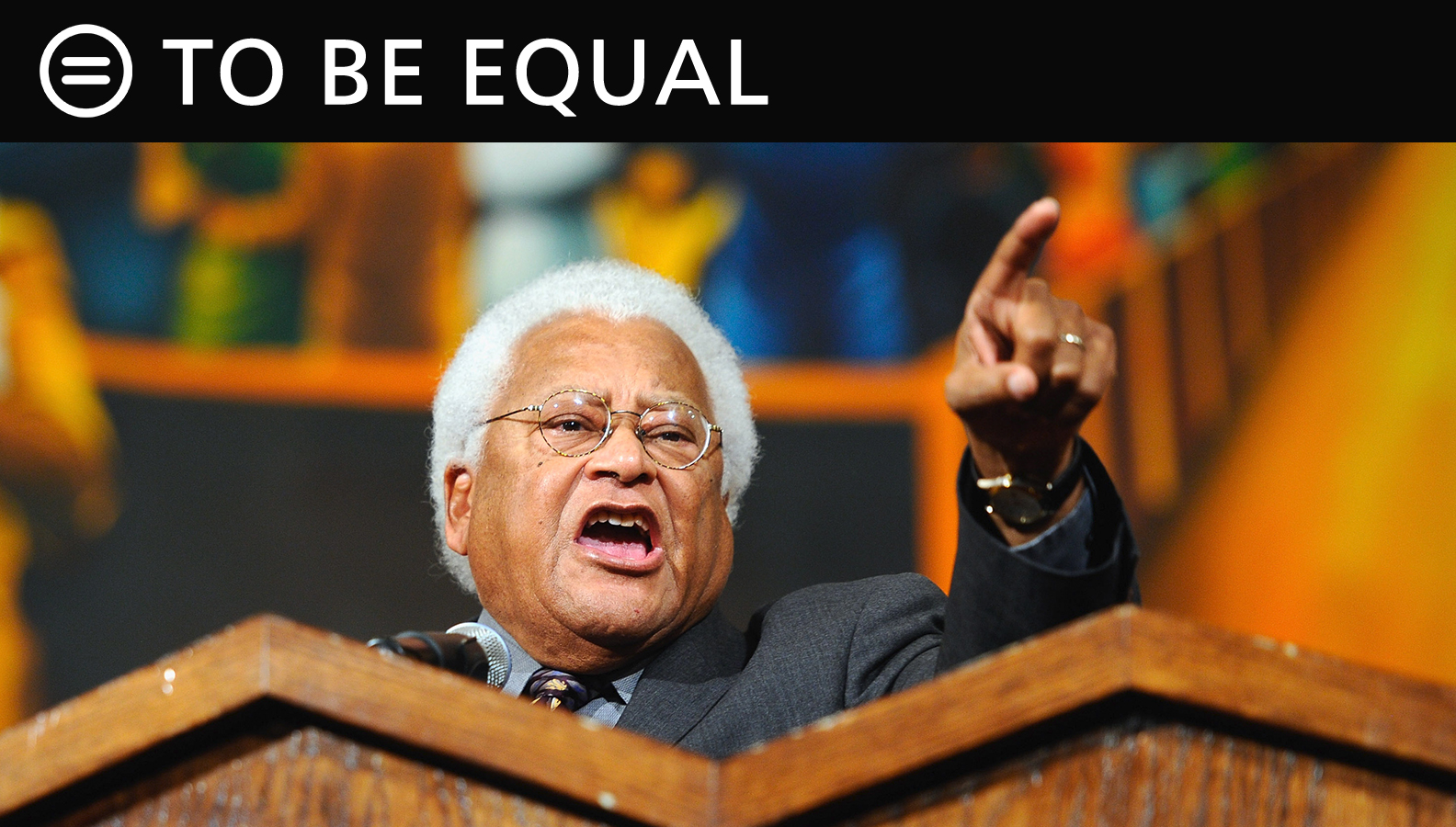

Rev. James Lawson, An Unsung Hero Of The Civil Rights Movement

Marc H. Morial

President and CEO

National Urban League

“Through nonviolence, courage displaces fear; love transforms hate. Acceptance dissipates prejudice; hope ends despair. Peace dominates war; faith reconciles doubt. Mutual regard cancels enmity. Justice for all overthrows injustice. The redemptive community supersedes systems of gross social immorality.” – Rev. James Lawson

History attributes the success of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th Century to nonviolence. The stoicism and quiet dignity of the marchers, the Freedom Riders, the lunch counter sitters stood in stark contrast to the brutality of the segregationists. Scenes of the confrontation, beamed via television into America’s living rooms and splashed across newspaper pages, shocked our collective conscience and galvanized support for the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act.

No one can claim more credit for that hard-won success than Rev. James Lawson, who passed away last week at the age of 95.

He was a driving force behind most of the major civil rights action of the era, His seminars on non-violence steeled young demonstrators against the inhuman violence they were to experience. He sought understanding and reconciliation with those who opposed him.

He also was a friend to the Urban League who frequently attended the Los Angeles affiliate’s annual Whitney M. Young, Jr. Awards Gala.

Lawson’s serene and disciplined courage is recounted in David Halberstam’s book on the Nashville Student Movement, The Children:

“ … he was enraged by Lawson’s coolness and he spat at him. Lawson looked at him and asked him for a handkerchief. The man, stunned, reached in his pocket and handed Lawson a handkerchief, and Lawson wiped the spit off himself as calmly as he could. Then he looked at the man’s jacket and started talking to him. Did he have a motorcycle or a hot-rod car? A motorcycle was the answer. Jim asked a technical question or two and the young man started explaining what he had done to customize his bike … In that brief frightening moment Jim had managed to find a subject which they both shared and had used it in a way that made each of them more human in the eyes of the other.”

His gentleness shrouded a fierce radicalism, which was instilled in him by his staunchly anti-racists parents. His minister father, a graduate of McGill University in Montreal, carried a pistol and taught his son to fight. But his mother, a Jamaican immigrant, was a pacifist. When his mother scolded him for slapping a white boy who called him the n-word, he vowed never again to resort to violence. He was 10 years old.

He stayed true to that vow when he received his draft notice for the Korean War. As a candidate for the ministry, he was eligible for deferment, which he considered a “moral and ethical sellout.” He served 13 months in prison for refusing to serve.

He was on a mission in India, studying satyagraha—Mohandas Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent resistance – when he read a newspaper story about the Montgomery bus boycott. “He began whooping, clapping, and dancing in joy,” according to Peter Drier’s The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame. “The photographs offered evidence that a nonviolent mass movement was taking hold back home. Moreover, the boycott movement was being led by a young Christian minister of about the same age as Lawson.”

In preparation for joining the Civil Rights Movement in the south, Lawson began work on his master’s degree in theology at Oberlin College. But in 1956, Martin Luther King, Jr., came to speak at Oberlin. The two bonded over Ghandi’s teachings, and King persuaded Lawson to join him immediately. He transferred to Vanderbilt University in Nashville and began conducting workshops on nonviolent protest for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

His commitment to reconciliation extended even to the man convicted of King’s assassination, James Earl Ray, whom he ministered in prison.

“The motivation was simple,” he said. “I did not see it as something apart from the love of God or the love of Jesus.”

###

25TBE 6/21/24 ▪ 80 Pine Street ▪ New York, NY 10005 ▪ (212) 558-5300

Connect with the National Urban League

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NatUrbanLeague

Twitter: https://twitter.com/naturbanleague

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/naturbanleague

Website: https://www.NUL.org

Newsletter: http://bit.ly/SubscribeNUL

YouTube: http://bit.ly/YTSubNUL