The Meaning Of The Brown Decision [May 10, 2004]

May 17, 2004, this coming Monday, is a school day, a work day.

Which is appropriate because the decision the U.S. Supreme Court handed up fifty years ago on the May 17 of 1954 in the landmark school segregation case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka set out a lesson a large number of the citizens and the state and local governments of the United States of America had long refused to learn.

And, today, albeit the wonderful progress made, American society is still a considerable distance from the end of the learning curve that would make the promise of Brown a reality.

No one better expressed that promise than Martin Luther King, Jr. would nine years later when at the 1963 March on Washington he spoke of his “dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

- “I have a dream,” he declared, “that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.

- “I have a dream,” he continued a moment later, “that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

- That those who believed the opposite of the vision King proposed as America’s destiny later tried to hijack that particular passage for their own ideological ends testifies to the power King’s vision had and has.

- That’s because there was no better expression of the American dream and of the best of the American character than the movement, the twentieth-century African-American civil rights struggle, which King led in its climatic phase.

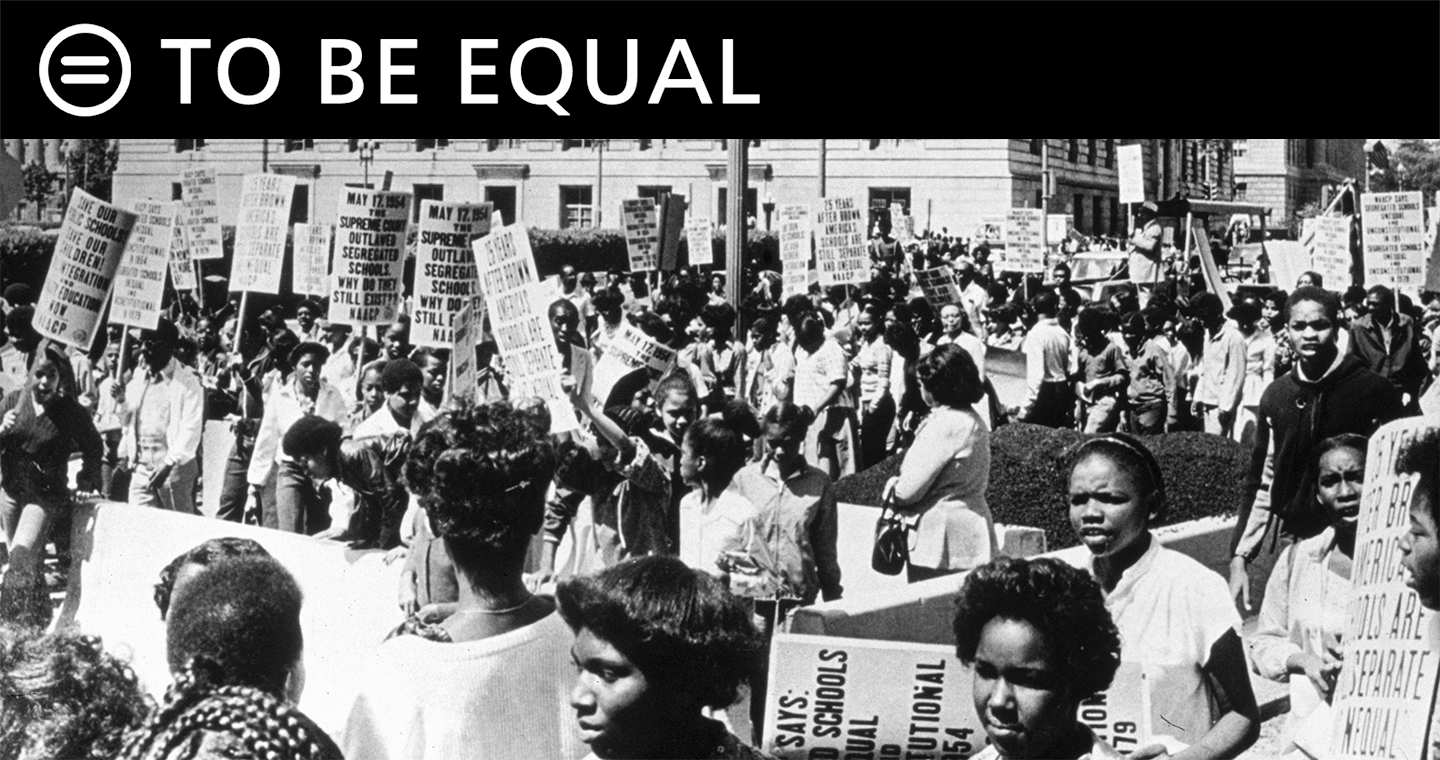

- Despite a “massive” and violent resistance from individuals and local and state governments alike, that nonviolent movement exploded across the segregated South in the mid-1950s after the Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

- Black America and the rest of America, too, has long since come to realize that, in actual terms, the Brown decision itself has a profoundly complex legacy. It was not the last stop before the Promised Land.

Indeed, numerous civil rights movement veterans, including some who were part of legal team that took Brown and its companion cases to the Court have long noted that the promise of Brown—equal educational opportunity across the color line—remains unrealized. So have others with impeccable civil rights credentials.

Harvard Law School professor Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., whose new book on the Brown case was published this month, pointed out Thurgood Marshall and the rest of the civil rights community immediately understood the true meaning of the Court’s fateful addendum that the schools were to be desegregated “with all deliberate speed.”

It meant, Ogletree writes in the current issue of our scholarly journal, The State of Black America 2004, “the resisters were to be allowed to end segregation on their own timetable.”

Ogletree’s analysis was complimented in the pages of Opportunity Journal, our general-interest magazine, by equally keen examinations of Brown by New York University law professor Derrick Bell, the Honorable Constance Baker Motley, the former Chief Judge of United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, John Hope Franklin, the noted historian, and Professor Gary Orfield, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Their words leave no doubt that the White South’s ten-year campaign of massive resistance to civil rights for African Americans blocked all but token progress on the schools’ front. They also bluntly say that, except for a brief period in the late 1960s, the Supreme Court’s hostility to implementing Brown in both the South and the North undermined its execution even more.

But they agree that it would be wrong to write off the importance of Brown decision. For it was a ruling that beyond the schools has had an enormous impact on American society.

By destroying—at least on paper—government-sanctioned segregation, and declaring that it was time for America to not merely pledge allegiance but actually live out the “self-evident truths” of the American Ideal, it prepared America for what was to very shortly come.

That was the work, along the civil rights trails of the South and the North, of black Americans and their allies among other Americans that matched the determination and vigor and courage shown by the heroes of Brown—the children and families and lawyers and activists, most of them still far too little known, who gave the Supreme Court, and the nation, the chance to redeem America’s honor.

That work—the work of redeeming America’s promise by providing equal educational opportunity for all—continues.

That, too, is part of the legacy of Brown.